As DeFi and NFT communities grow enormously in size, how to govern decentralized protocols takes on added importance. Now and over the next few years, one of the most immediate challenges facing these communities is to figure out governance — the act of managing collective decision-making in order to optimize funds and operations.Governance requires significant coordination costs, however, arising from the need to have network participants involved in voting on every decision made. These coordination costs can be radically reduced in new types of decentralized networks, in which smart contracts enable participants to govern cooperatively.These new networks are called DAOs (decentralized autonomous organizations) — collections of people coming together with aligned incentives and common interests, with no one leader or single point of failure, and run almost entirely by code. Many new protocols are being built using this structure, with much of the activity so far in open-finance-based systems, but also, increasingly, in cultural networks purchasing and trading art and other collectibles. In many ways, DAOs can be viewed as an amalgamation of pieces of investment banks, companies, and social clubs, stitched together via cryptographic commitments. Despite the moniker, DAOs are typically not completely autonomous — someone needs to create decision frameworks to ensure a DAO is governed effectively and financially incentivize network participants to participate so the DAO can grow. Many questions greet DAOs creators and participants, then: What are the decisions that need to be made? What kinds of financial incentives can be used? Under what conditions should DAOs be formed? What are the main governance tasks that are required today? And what tools can be used to help govern?Before we answer those, let’s ask another question — how did we get here? — and briefly explore the development of DAOs. This will allow us to see how decentralized structures have formed and changed in the last half-decade, helping explain why financial incentives are a key factor in the coming age of DAO governance.

Experiments paved way for modern DAOs

The world first heard about these internet-native organizations in 2016. “The DAO,” as the most well-known early DAO was called, was a collective investment vehicle that aimed to be a rationalist form of crowdfunding — a sort of decentralized venture fund — and provided the first glimpse of how such a decentralized organization, run via code, could govern itself. Participants supplied ETH to The DAO and received DAO tokens. These tokens represented holders’ economic interest in The DAO as well as voting rights. The DAO’s dream was to allow any participant — regardless of how small or large their contribution to the treasury was — to earn significant rewards in the Ethereum ecosystem. A critical smart contract bug led to the funds in the DAO contract being drained by an attacker, and the term DAO went out of favor, leading to the “DAO winter” that coincided with the post-2017 bear market. With lessened expectations and less attention, a number of important experiments in governance during this period paved the way for modern DAOs. The first of these addressed the problem of security — no network can function, let alone grow, if users are worried their funds will disappear. First, Ethereum competitors such as Tezos promised safer smart-contract programming languages that would make avoiding The DAO’s issues easy for developers. On Ethereum, a number of experiments such as Aragon, dxDAO, Kleros, and Moloch emerged. These DAO implementations brought better programming standards and experiments with new token distribution mechanisms to the space. With security concerns lessened, the biggest issue common to early DAOs was that they were then unable to find an incentivization model that encouraged high voter participation in DAO affairs. Without participation by voters with specialized knowledge needed to make informed decisions, DAO governance stalled.

The rise of financial incentives

The rise of DeFi (decentralized finance) in recent years has opened the door for more sophisticated open-finance systems and tools that don’t rely on banks and other legacy systems. New DAOs began to emerge that used financial incentives to encourage participation in these systems. These incentives, and the ways in which they have built upon one another, have become crucial for DAO governance — without financial incentives, network members have no reason to put their time, money, and energy into networks, vote on proposals to improve them, or care at all about their continued growth and success. Here are several types of incentives, and some of the key events in their formation, to help builders understand how we got here, when DAOs are needed, how incentives are crucial for governance, and the tactics for effectively governing DAOs.

Growth incentives

An important development came in June 2020, when Compound, an on-chain lending protocol, decentralized itself — its core developers turned over the operation and ownership of the network to the community. Unlike prior DAOs, the Compound Governance DAO gave the community members control of the protocol’s reserve assets that are generated via fees from borrowers. These cash flows were (at the time) the highest revenues ever generated by an on-chain protocol.Compound came up with a novel token distribution model that aimed to both incentivize capital growth within the protocol and provide users better pricing on loans. This model involved continuous distribution of Compound’s native tokens (COMP) to users who provided liquidity to the protocol and took out loans from the protocol. Every user of Compound instantly became a stakeholder, with some of them becoming active contributors and voters. These financial incentives were crucial for controlling key parameters such as margin requirements and interest rates. Compound’s distribution offered a glimpse of the decentralized dream — control of the protocol (and its cash flows), by users of the protocol. And as the Compound protocol had billions of dollars of assets and liens that needed governance, the primordial settings for a new type of DAO were set — participants had clear reasons to act in the best interests of a network, with their time, assets, and votes, because the growth and success of the network could benefit them personally.

Yield farming

The development of governance token distribution, given to users of a protocol rather than only investors and the development team, created a design space for many new models to occur. First was the creation of various incentivized actions on a protocol — “yield farming.” Yield farming occurs when users are rewarded for performing actions like lending, borrowing, staking, or providing other forms of asset liquidity — and the reward comes in the form of a token that represents a piece of ownership of the protocol itself. Recipients can either accumulate that ownership, counting on a rise in the value of the protocol, or they can sell it on the open market, compounding their action and increasing their yield. Imagine if major banks gave you a small share of their stock each time you made a deposit — you’d be more likely to make deposits, which would be good for you and the bank.Compound users, for instance, could achieve a form of yield by locking up their capital in the protocol (i.e., using it as collateral to transact in the protocol through borrowing and lending) and earning denominated DAO governance tokens. In this way, Compound was able to use COMP to incentivize growth and create a user base incentivized to vote on and contribute to the protocol, as the promise of yield drew more users. Once developers realized that they could attract capital to new DeFi primitives via yield farming, there was a race throughout the summer of 2020 to grow DeFi protocols via DAO governance token distributions. The summer’s catalyst for growth was the launch of DeFi yield aggregator Yearn Finance (YFI), whose “fair launch” (in which all tokens are distributed to capital providers and none to developers), shifted the narrative away from VC-funded projects to community-funded projects. Once YFI launched and achieved rapid growth, numerous competitors launched clones and knock-offs promising slight improvements but, more importantly, new DAO governance tokens. YFI demonstrated that the promise of governance alone could bootstrap network adoption. The fair-launch model, and its use of initial token distribution to target the ideal future users, has since become prevalent.

Retroactive airdrops

New protocols have built on these models to further incentivize users. A prominent example is the airdrop, or delivery of tokens to current or former users’ wallets to spread awareness, build ownership, or reward early users retroactively. Decentralized trading protocol Uniswap, for example, launched the UNI token, which was retrospectively granted to everyonewho had ever used the Uniswap protocol. This airdrop led to some early users earning tens of millions of dollars worth of UNI. More importantly, the airdrop and token launch turned out to be an effective capital protection weapon that soon became necessary for new DeFi protocols looking to gain market share.The increase in token issuance also led to a change in governance power — early users, who had no idea that their participation would lead to governance rights, began to own significant portions of networks, thereby promoting greater decentralization. The retroactive airdrop became a tool for increasing both token distribution and governance participation from active users.

Cultural DAOs and Gaming Guilds

The development of financial incentives outlined above contributed to the exponential growth of DeFi protocols over the last year. Other types of DAOs are also emerging, however, with different cultures, incentive models, and governance structures. Recently we’ve seen the rise of DAOs with token distribution models that (unlike DeFi DAOs) aren’t tied to usage or participation. These are collector DAOs, made up of people who make decisions to collectively purchase art or other digital items. An example is PleasrDAO, which formed in the wake of the creation of a commemorative video created by pplpleasr, née Emily Yang, for the launch of Uniswap V3 (I’m a genesis member of PleasrDAO). That video was viewed as the iconic art that captured the spirit of DeFi in 2020. An NFT was minted for the video and auctioned, with proceeds going to charity. This auction and the collective ethos around the artwork led a number of long-time DeFi developers and entrepreneurs to create a DAO to purchase the art. PleasrDAO’s advancement was a unique mechanism for fractionalizing NFTs that made collective ownership of a single artwork much more feasible. This vision portrays the DAO as an art museum, like MoMA, albeit where all of the pieces in the museum could be collectively owned by patrons.Another culturally significant collector DAO, arising in Fall 2020, was FingerprintsDAO (of which I’m a member). Unlike PleasrDAO, FingerprintsDAO focuses on building a collection of generative and on-chain art. NFT-based generative art is unique in that it allows for the artwork to change every time ownership is changed — for instance, artworks such as $HASH (Proof of Beauty) where the underlying metadata randomly changes as a function of blockchain state every time the artwork is transferred. FingerprintsDAO collects such artworks and has some of the largest collections of Autoglyphs, Bitchcoins, and 0xDEAFBEEF.FingerprintsDAO and PleasrDAO utilize their DAO governance token to manage their treasury, perform asset sales (including proceeds from fractionalization), and for asset curation. DAO tokenholders have the right to vote on these issues and in many cases, the outcomes of these votes are directly executed on-chain algorithmically using DeFi protocols such as Fractional or Uniswap. Because collector DAO token distribution isn’t linked to usage or participation — and financial incentives aren’t as aligned as they typically are with DeFi DAOs — it can lead to early DAO organizers taking on larger and larger commitments to keep the DAO operating effectively, as well as complicated dynamics among DAO members. This alignment challenge is specific to cultural DAOs, and builders in this space should use different types of governance tactics to keep DAOs running efficiently.One way is for collector DAOs to employ full-time engineers and product managers who are directly incentivized using the DAO governance token (while making sure such organizational structure maintains the decentralized governance and operation of the DAO). By ensuring that those who are working for the DAO are able to earn an increasing share of the DAO’s assets, one can create a stable equilibrium between early tokenholders and those working on the day-to-day management of a DAO. A final type of DAO, with its own culture, incentive models, and governance structures, is the gaming guild — a DAO-ified version of gaming clans (basically, groups of players who play as a team). These decentralized guilds collectively own game items and/or collectibles, and share in their usage and proceeds when sold. Unlike in traditional gamer guilds, play-to-earn mechanics found within games like Axie Infinity can encourage cooperative strategies and revenue sharing amongst participants. These mechanics make them more like DeFi DAOs — participation in the network earns rewards while also boosting the network’s prospects — but to this point the governance of the networks are less tied to pure financial metrics and more tied to game performance and social metrics. These DAOs are important to watch, because as they evolve, they may find new mechanisms to increase their decentralization in ways that haven’t been used in other DAOs.

When DAOs are needed

The growth of DAOs in general and the massive success of some of the most innovative ones inevitably results in the perception that the route to growth and robust network participation requires a DAO structure. In times of ebullience, market forces make it easy to assume that every organization, community, or project needs a DAO, much as we saw in 2017 with crypto tokens in the ICO boom. But that’s not necessarily true. DAOs work best when the governance burden related to curation, security, and risk can be reduced faster than the natural increase in coordination costs that accompanies the need to have members involved in voting on every decision made. That’s why it’s important that protocol builders assess the real goals of the organization when deciding whether to form a DAO.The governance areas that are common to all DAOs are:

- Collective asset ownership and management. DAO treasuries and balance sheets should function like decentralized corporations with considerations of assets and liabilities, liquidity, income, and where to allocate financial resources.

- Risk management for assets. Volatility, price, and other market conditions necessitate continuous monitoring.

- Asset curation. From collected artwork to collateral for lending, all DAO assets benefit from goals and process around curation.

One should form a DAO only when it is clear that all of these governance areas are demanded by a community. It is important to note that while a DAO might focus on a subset of these activities, it really needs to provide all three functions. For instance, suppose that a cultural DAO owns an asset that it suddenly has the opportunity to earn proceeds or yield from. Even if the DAO completely ignored risk management until that point (e.g. focusing solely on asset curation), it faces this challenge upon such a sale. One of the most prominent examples of such an event was PleasrDAO’s $225m sale of the $DOG token, which represented fractionalized ownership in the original Dogecoin meme NFT. Until this point, PleasrDAO focused solely on asset curation and ignored issues of risk management. Launching the token via Sushi’s Miso platform forced the group to learn about different token distribution mechanics and economics, especially as the fractionalized NFT market structure is nascent. The group also had to ensure that community members felt real ownership in the NFT by instituting a community development fund. The key lesson here is that DAOs will need to add new collective skills and governance processes as their activities change, and that successful DAOs will recognize shortcomings quickly.

The three key governance areas

Growing DAOs will likely reach the point where their communities demand governance structures for all three of the key needs. Below, I share a more detailed breakdown of each of them to help builders/protocol developers clearly identify where they will have to put their focus if they want to build a successful DAO.

Collective asset management

All DAOs are seeded with some initial capital, in the form of governance tokens held by the DAO smart contract and assets used to purchase governance tokens. For instance, if a DAO starts by minting 1,000 governance tokens and sells 500 of them to genesis members for 100 ETH, then the DAO’s initial treasury consists of 500 governance tokens and 100 ETH. However, as a DAO grows in terms of users or accumulated cash flows (e.g. Compound), it becomes important for communities to manage their capital much like a company, because corporate governance best practices lend themselves well to DAOs, with the added difficulty of less privacy.

Risk management

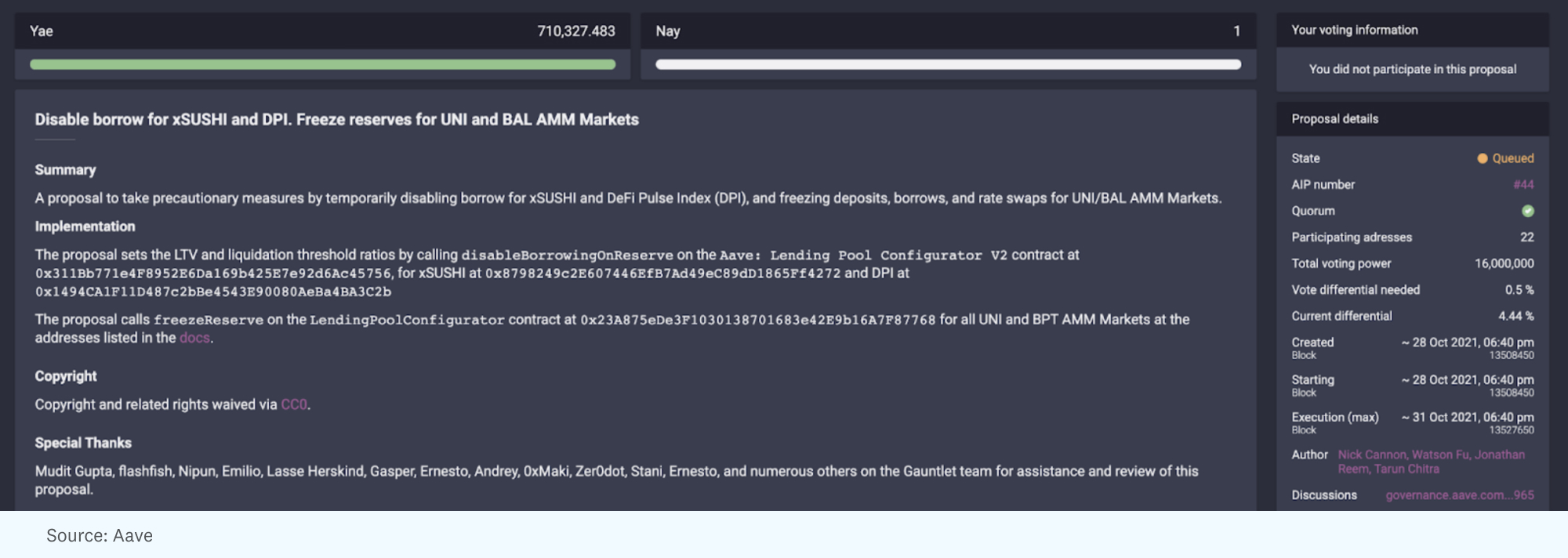

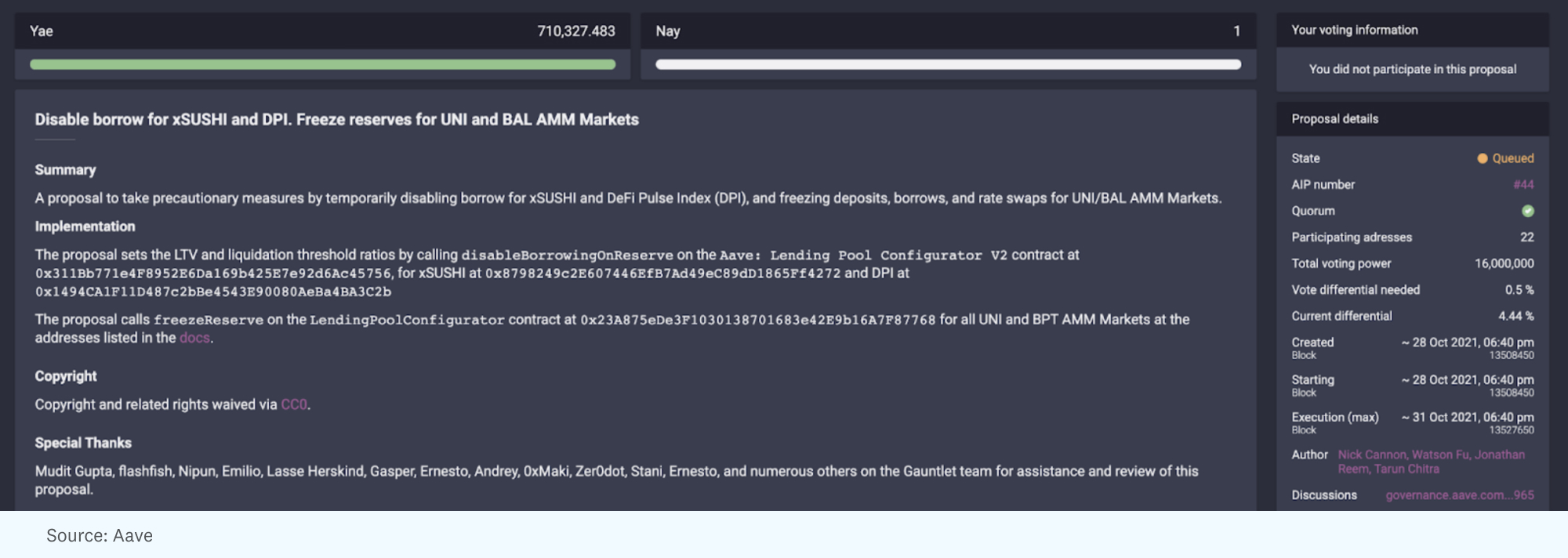

As the balance sheet of a DAO is generally made up of risky assets, managing a DAO’s currency exposure to ensure that future operations can be funded becomes increasingly important. A number of DeFi and NFT DAOs have treasuries consisting of hundreds of millions or billions of dollars of assets. These assets are meant to be used for funding development and audits, providing insurance should an underlying protocol fail, and for spending on user growth and acquisition. In order to meet these goals, DAOs need to manage treasuries to meet particular metrics or key performance indicators (KPIs), such as, “Can we survive a 95% drawdown in asset prices?” or “Can we still purchase NFTs of high value if we earn X% interest on our holdings?”Here’s a recent example of how this looks in practice: Network participants in Aave, a decentralized money market protocol, last week identified potential vulnerabilities in using xSushi as collateral within the protocol, due to an oracle mispricing issue (which was exploited in CREAM Finance for $130 million). Gauntlet ran simulations to assess the threat, and found that under current market conditions potential attackers would not be able to succeed in manipulating the currency. As an added precaution, Gauntlet put forth a proposal in Aave governance, which was overwhelmingly approved by participants, to disable certain types of borrowing to mitigate the risk. (Aave’s DAO is a Gauntlet client.) Here we see three key governance dynamics at play — a financially aligned community sensitive to potential threats, modeling to assess the true nature of the threat, and a governance process in place to make necessary changes (with a bias toward security).

Here we see three key governance dynamics at play — a financially aligned community sensitive to potential threats, modeling to assess the true nature of the threat, and a governance process in place to make necessary changes (with a bias toward security).

Asset curation

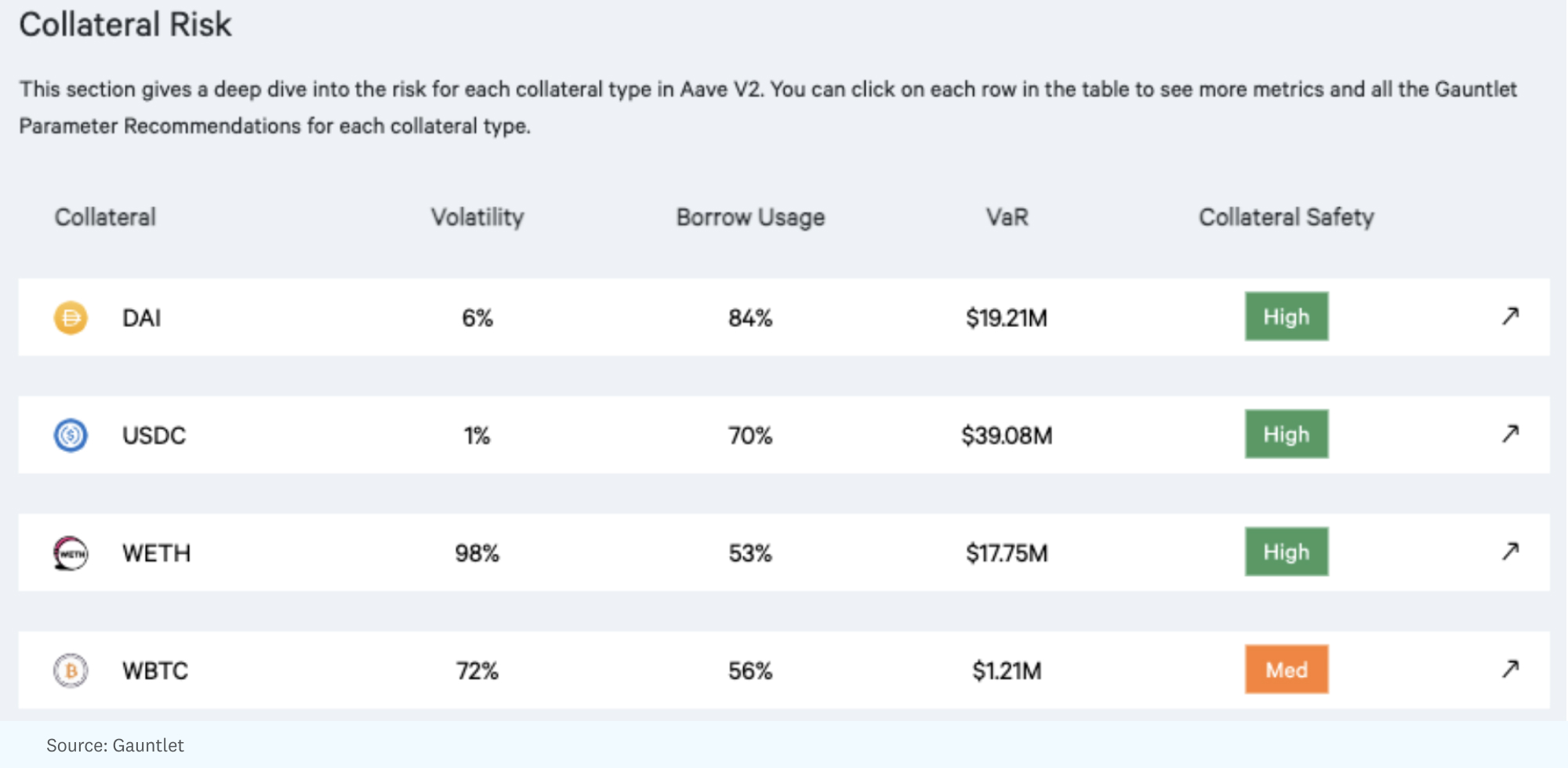

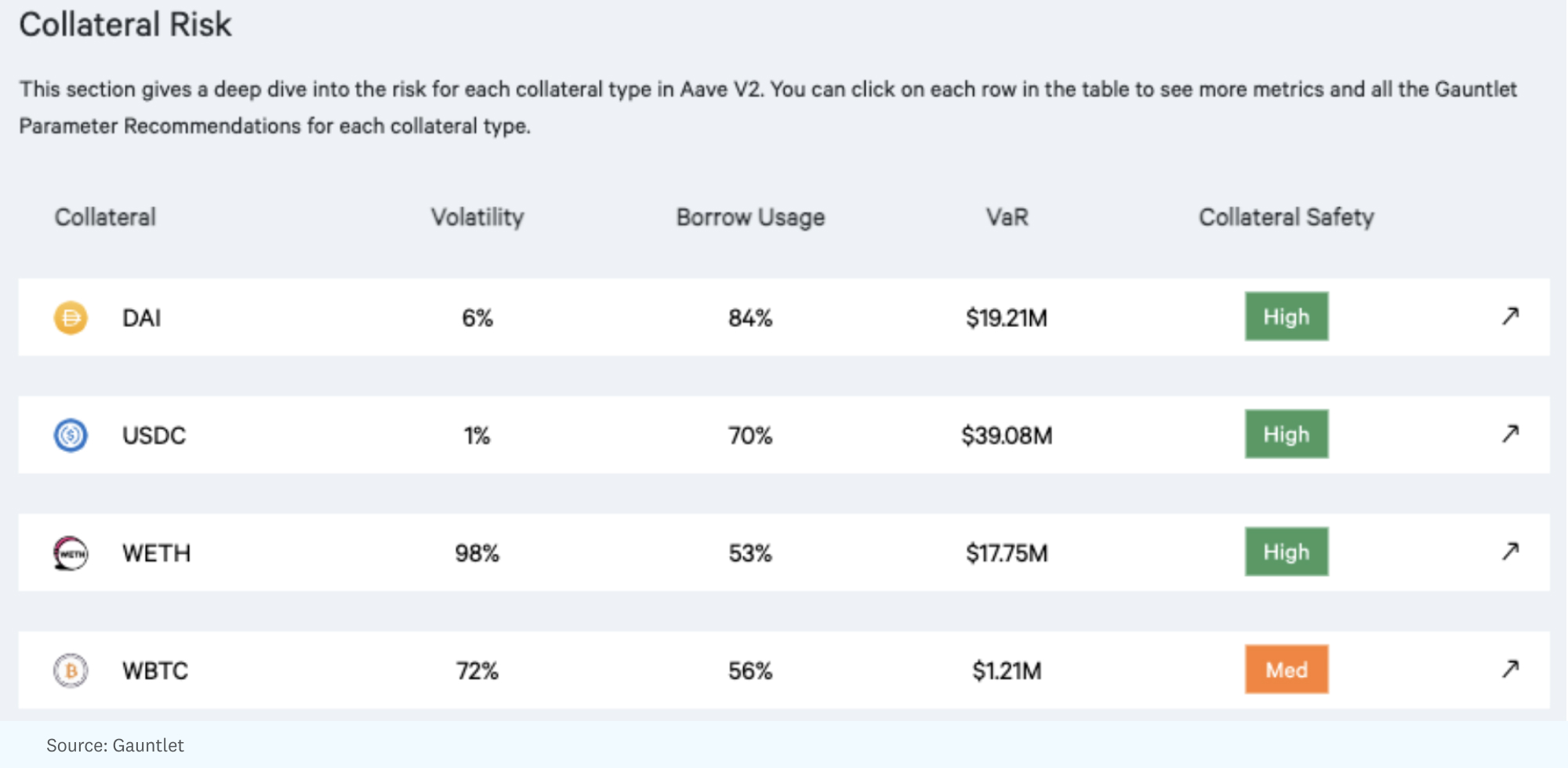

The most natural place for asset curation is NFT collection DAOs, such as PleasrDAO. These DAOs naturally act as art and culture curators, with the DAO governance token utilized for voting on adding or removing assets. However, DeFi DAOs often face this problem as well. While some mechanisms, such as Uniswap, allow for permissionless asset addition — anyone can create a trading pool with a new asset — others that have leverage cannot do the same. In particular, lending protocols like Aave and Compound utilize governance to decide which assets can be added or removed. This is because a number of parameters must be chosen for each asset — margin requirement, interest rate curves, insurance costs — and the decisions are crucial for protocol safety. Let’s provide a simple example of what can go wrong. Suppose that we mint a new asset — TarunCoin — where I am the owner of 100% of the TarunCoin supply. Now suppose that I create a lending pool that allows me to borrow against 100% of TarunCoin’s value. If I control the price of TarunCoin to USD (e.g. via a Uniswap pool where I am the only liquidity provider), then I can make TarunCoin’s market capitalization really high (say $100M) and then borrow $100M in USD against TarunCoin. However, when my loan inevitably defaults as there is little to no TarunCoin liquidity, then the lenders who pooled assets together to lend me $100M take the loss.This example illustrates that asset quality — measured in terms of token distribution, liquidity/ease of price manipulation, and historical volumes — is crucial for DeFi DAOs that utilize leverage. As many such DAOs use their governance token as an implicit or explicit insurance fund to pay back lenders should an adverse event occur, it is crucial for such DAOs to be careful which assets they admit and how the parameters for those assets are chosen. As the space evolves, it is likely that insurance products will help improve and reduce the amount of governance intervention needed for asset curation in DeFi.

Ways to run a DAO

A natural follow-up question is: “How can our community actually do these three tasks? Our community only cares about X.” As DAOs mature, there is an ever-growing ecosystem of companies and protocols that aim to lessen the load on DAO members by automating analysis and monitoring and aiding careful asset and parameter selection. And there are tactics that can reduce complexity within DAOs and allocate resources more efficiently. Here are some of the steps DAOs can take:

Use governance tools

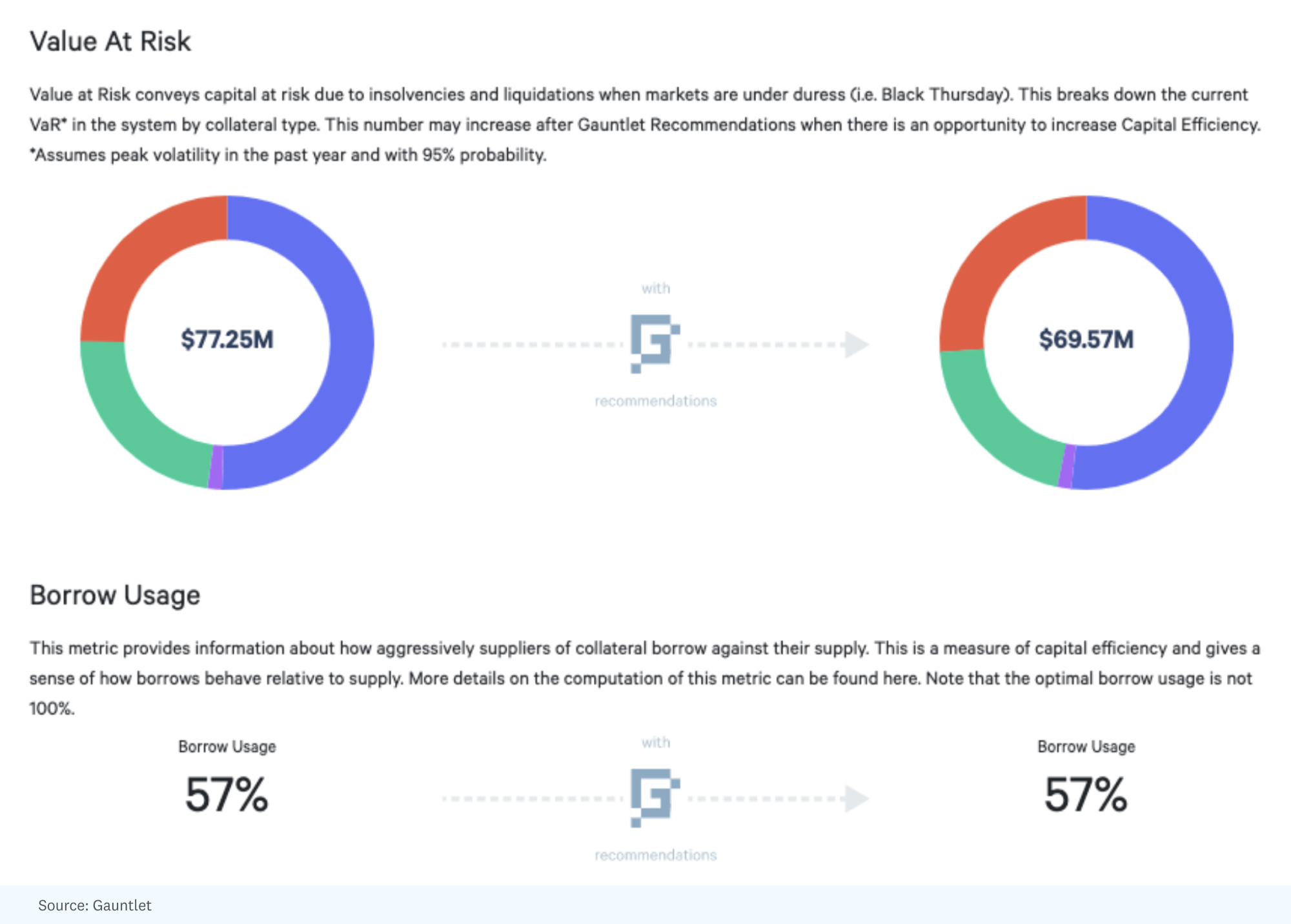

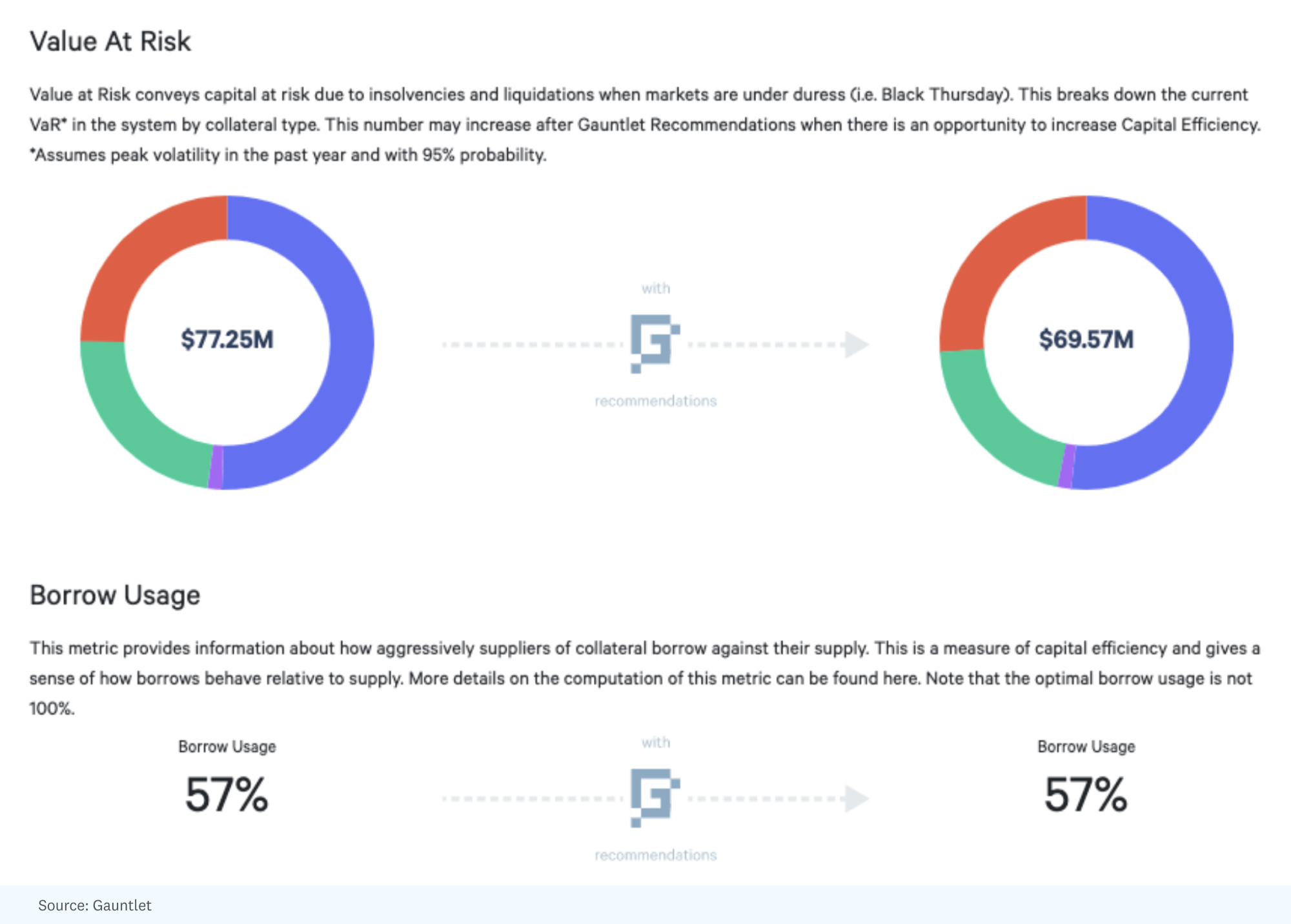

First, quantitative tools have emerged that let your community visualize the risk in the DAO (and potentially, the associated protocol) as a function of market conditions and let DAO members understand what it means to vote on reducing collateral/margin requirements or increasing an interest rate, for example. This provides greater transparency into the level of risk held by a DAO treasury and allows the community to update treasury composition to meet specific KPIs. The billions of dollars of assets held by lending protocols Aave and Compound, for example, effectively act as an insurance backstop for the underlying lending protocols. For instance, if there is a large price disturbance that causes a large number of loans to default, causing losses to lenders in the protocol, these DAOs can use their treasuries to make lenders whole (see, for example, the Compound DAI liquidation event). Adjusting parameters in the protocol, such as collateral requirements, helps reduce the likelihood of the DAO having to spend its treasury on such backstop events. Below is an example of a live dashboard for monitoring risk in different Aave markets. (Disclosure: I am the founder and CEO of Gauntlet, which provides these services). The tools used to quantify risk include simulation tools that combine tools used in algorithmic trading and AI (e.g. AlphaGo).

The goal of such tools and services is to allow for communities to scale to larger and more diverse populations. As protocols become increasingly complex and intertwined due to smart-contract composability, governance becomes incrementally more difficult for each new member. This, in turn, makes it harder for new members to join a DAO and participate in a meaningful manner. By helping users simply interpret the complex behaviors hidden within a DAO, visualizations can help with new member onboarding. For instance, tools can allow all members to understand what they are voting on without needing to understand underlying technical intricacies. Each DAO tool or service can then specialize in providing interpretable, easy-to-understand dashboards of a DAO’s health from technical, financial, and community perspectives. Within DeFi, the main issues that DAOs tend to deal with involve financial and technical risk, hence their tokenholders use tools to assess such risks. They can also help proxy voters (e.g. voters who delegate their voting rights to another voter) assess how well their proxies are doing in improving protocol performance.

The goal of such tools and services is to allow for communities to scale to larger and more diverse populations. As protocols become increasingly complex and intertwined due to smart-contract composability, governance becomes incrementally more difficult for each new member. This, in turn, makes it harder for new members to join a DAO and participate in a meaningful manner. By helping users simply interpret the complex behaviors hidden within a DAO, visualizations can help with new member onboarding. For instance, tools can allow all members to understand what they are voting on without needing to understand underlying technical intricacies. Each DAO tool or service can then specialize in providing interpretable, easy-to-understand dashboards of a DAO’s health from technical, financial, and community perspectives. Within DeFi, the main issues that DAOs tend to deal with involve financial and technical risk, hence their tokenholders use tools to assess such risks. They can also help proxy voters (e.g. voters who delegate their voting rights to another voter) assess how well their proxies are doing in improving protocol performance.

Partition into “subgroups”

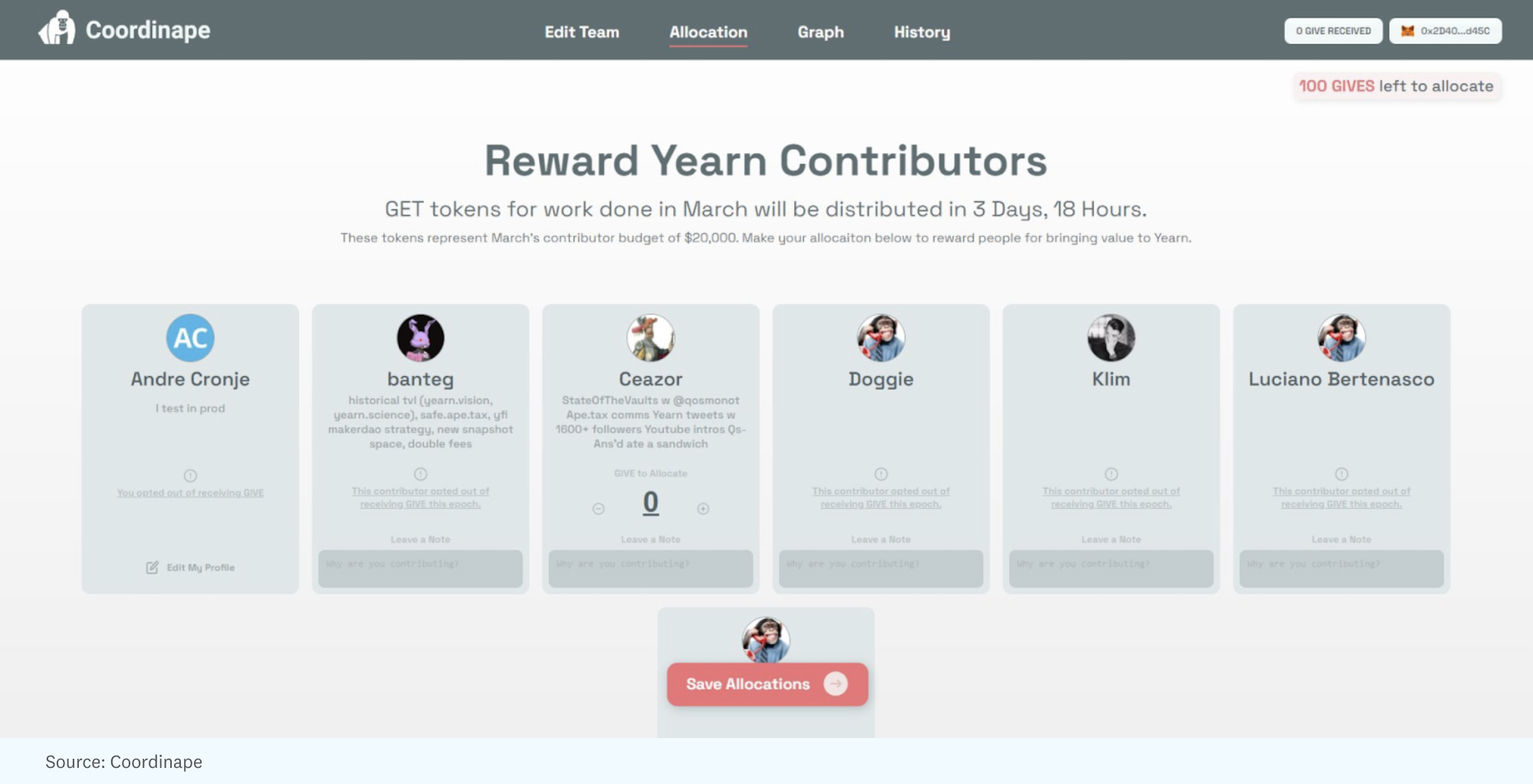

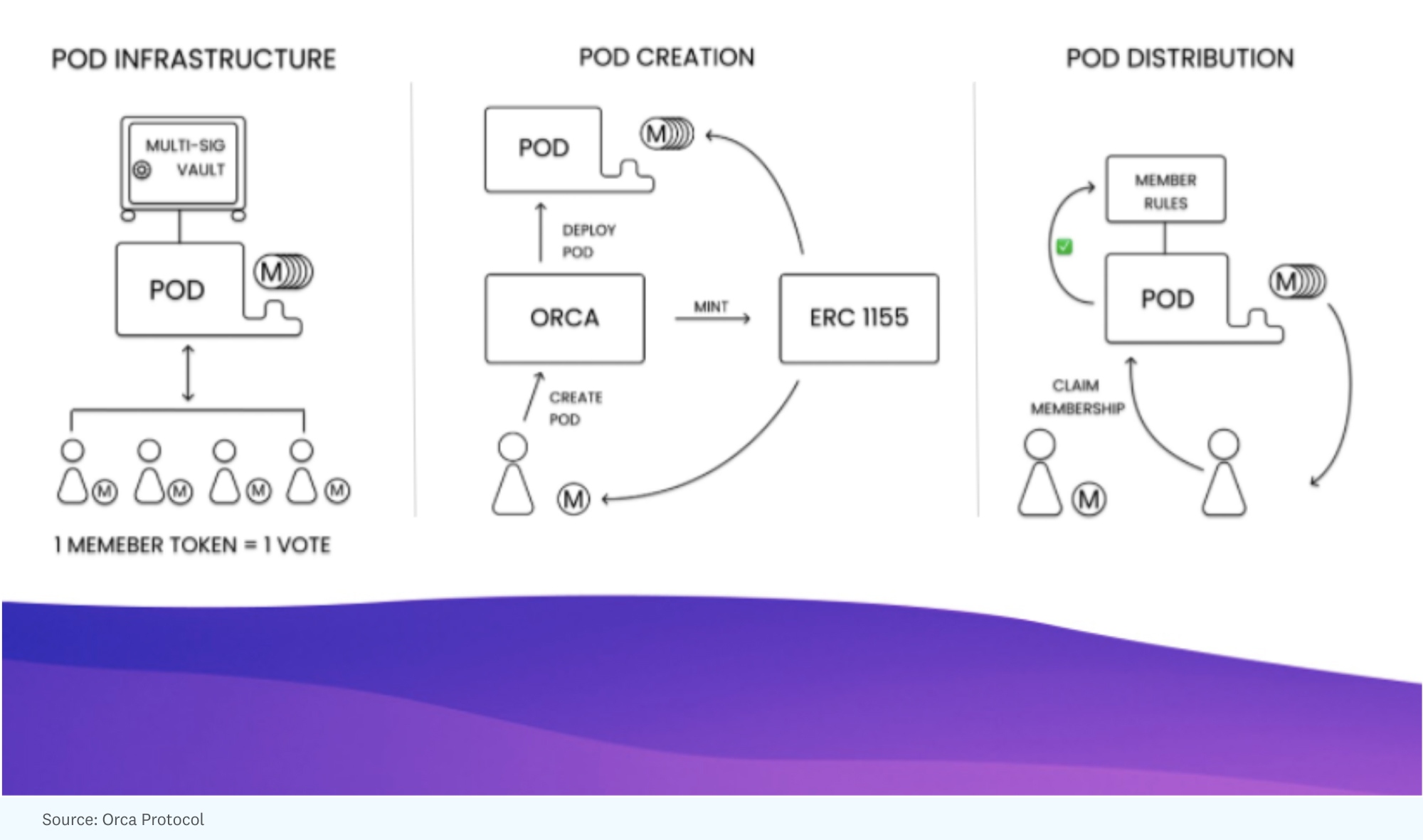

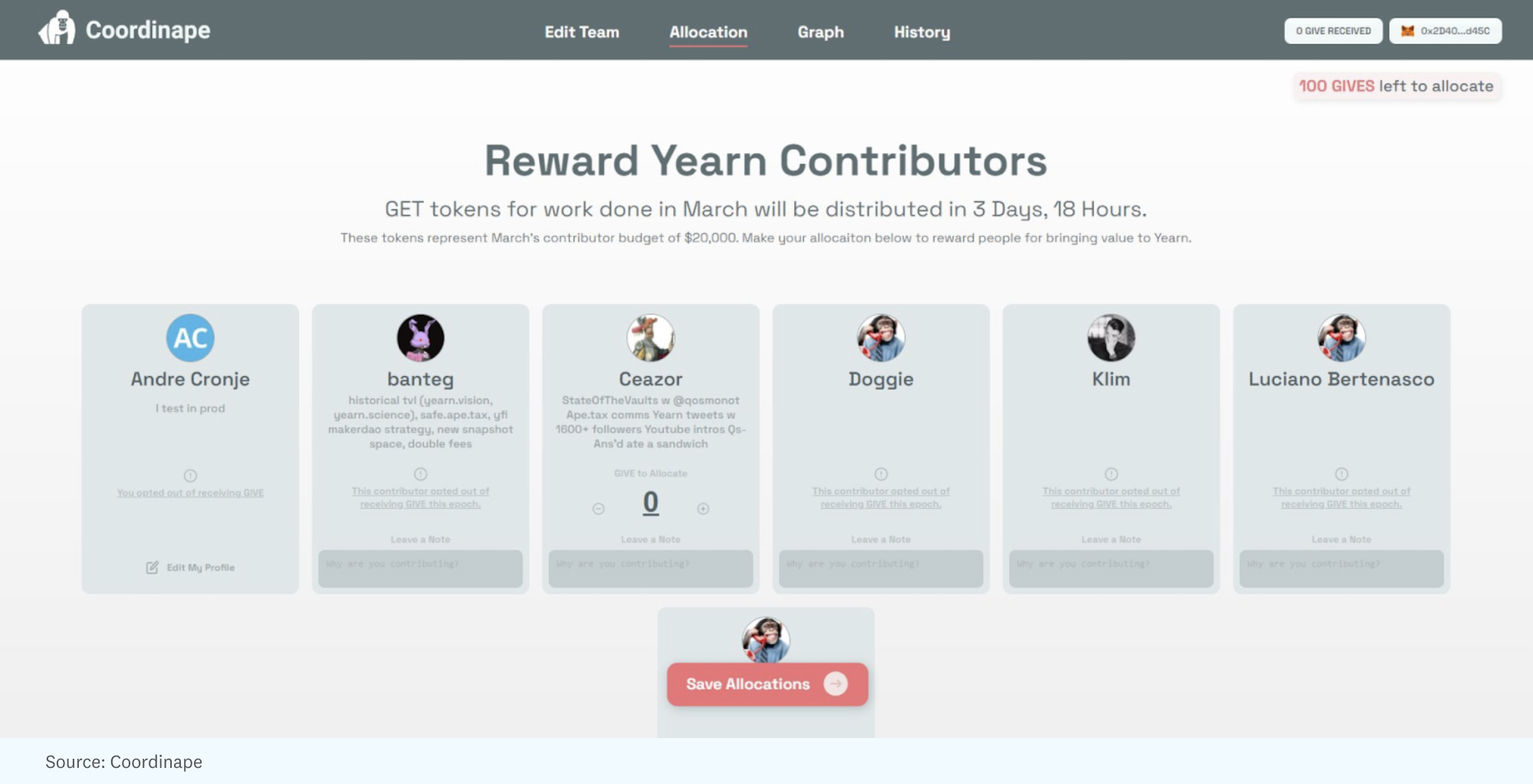

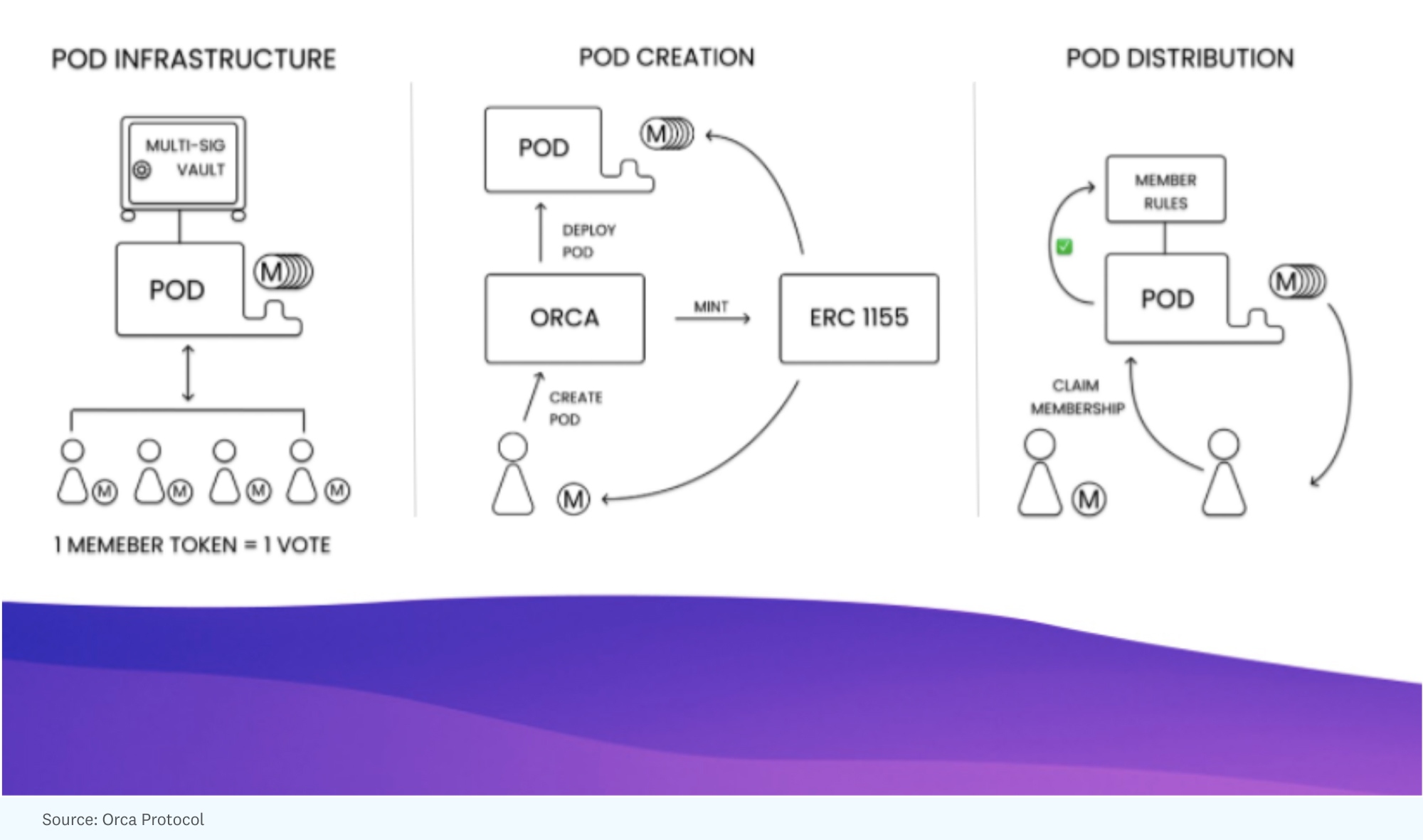

Another potential tactic that can help expand a DAO’s membership and scope ispartitioning a DAO into subgroups that each operate independently and focus on specific tasks (development, marketing, etc.). One of the first DAOs to partition itself successfully was Yearn Finance. Yearn’s rapid growth and constant product evolution led to a need to split up the team into multiple teams that independently handled tasks like front-end UX, core protocol development, and marketing. Early Yearn contributors tracheopteryx, zemm, and zakku created Coordinape, an “Asana for DAOs,” to help contributors coordinate. This product allowed DAOs to manage tasks and payroll across teams, time zones, and pseudonymous identities.  For a more decentralized approach, one can use DAO smart contracts to explicitly split up a DAO into teams. One can do this by allowing certain subgroups (known as sub-DAOs or pods), to call certain functions within the DAO’s smart contract. Orca Protocol has built tools around automating this procedure so that those without development experience can easily create pods. This protocol allows you to create authorized groups that can manage certain functions within a DAO, allowing different subgroups of your community to operate each of these tasks independently.

For a more decentralized approach, one can use DAO smart contracts to explicitly split up a DAO into teams. One can do this by allowing certain subgroups (known as sub-DAOs or pods), to call certain functions within the DAO’s smart contract. Orca Protocol has built tools around automating this procedure so that those without development experience can easily create pods. This protocol allows you to create authorized groups that can manage certain functions within a DAO, allowing different subgroups of your community to operate each of these tasks independently.

Hire staff

A final note about DAO governance: Once a DAO has a large enough community and assets, it’s important to hire people who can channel their energies full-time towards maintenance, communication, and administrative tasks. However, DAOs must take care not to create any “Active Participants” upon which token holders may be relying to drive the value of the underlying token. As a result, the addition of service providers must be done with decentralization in mind. DAOs that fail at hiring full time developers, community managers, and other staff often find themselves at a crossroads when their assets run dry or need servicing. Once-hot DeFi protocols ran out of steam as their DAO treasuries ran out, and no DAO member felt they had enough agency to ensure continuing operations (e.g. via protocol improvements or asset reallocation).While PleasrDAO has a council (much like a board of a company) that helps guide the long-term direction of the DAO, key contributors ensure that the launches, financing, and curation performed by the DAO are executed flawlessly. In this way, DAOs often can borrow from best practices of regular organizations too.

***

Coordinated efforts to form decentralized internet institutions that own assets are sometimes viewed as a “wild west” of uncharted territory. But many of the problems and solutions found in traditional systems — where humans also coordinate — can inform and guide DAOs; they’ve been pressure-tested for centuries, and can be adapted for this new world. In many ways, learning both from the past, and the recent history of DAOs, may help new builders find and adapt ideas for the future of online institutions.Acknowledgements:Thanks to John Morrow (Gauntlet), Nick Cannon (Gauntlet), Julia Rosenberg (Orca), John Sterlacci (Orca), Luiz Ramalho (FingerprintDAO), Jamis Johnson (PleasrDAO), and Robert Leshner (Compound) for helpful feedback and comments.